“Traveling these seas, the fleets and merchant ships of the ancient Greeks disseminated civilization and increased human understanding; they fought the barbarians, hindered the incursion of Asia into the West, and spread Hellenism as far as the shores of Asia Minor and Egypt, of Italy and France, and through all the Mediterranean. It might be said that from the start the sea was the spirit of Greece and the islands the embodiment of that spirit.”

George Theotokia’s “The Modern Greeks: An Interpretation of National Characteristics” 1955

Since Neolithic times, more than six thousand years ago, humans have occupied the rich coastal zones that surround the Mediterranean Sea on the shores of European Mediterranean countries, Turkey, the northern coast of Africa and the thousands of islands scattered throughout the Mediterranean, Aegean, and Adriatic seas.

The coastline of Greece is more 13,000 km long and comprises a full thirty percent of the entire Mediterranean coast. The Greek mainland of the Balkan peninsula and the Peloponnese that juts out below it are surrounded by more than a thousand Greek islands that Plato described as ants or frogs around a pond.

Mediterranean Sea Crete

The health of the Mediterranean Sea, including the waters surrounding Greece, is being severely compromised by human pressures: rapid urban and industrial development along its coastal zones, especially during the past 20 years, untreated discharges of waste into its waters from industry and cities, including heavy metals, runoff of nitrogen and phosphorous from the growing industrial-size farms along its rivers and estuaries and wetlands, pollution from plastics, and increasing ship traffic.

Climate change is causing record high temperatures on the land masses that surround the Mediterranean basin and the waters of the Med Sea are dangerously warming to temperatures not seen in thousands of years. Fish stocks, once plentiful, have been drastically depleted by overfishing.

I recently spent a month and a half traveling in Greece, with my wife, Susan, to conduct research for this article. We flew to Athens where we joined the crowds of visitors and climbed the steps to the Acropolis and walked through the Agora, the ancient meeting place, filled with spectacular ruins. Tourists filled the busy restaurants and outdoor cafes in the city’s lovely tree-shaded plazas.

We arrived in October, when the crowds of tourists were beginning to thin, but the air was still balmy and bright and the sea still warm enough for swimming.

After a few enjoyable days in Athens, we flew to Crete, the largest and southernmost island of Greece and halfway to the African coast where we spent three weeks driving across the dramatic, mountainous island. Then we flew to historic Rhodes in the Dodecanese group of islands off the southeastern coast of Turkey. After that we took a ferry to the rich agricultural island of Naxos in the Cyclades group, where for a week we explored the hilly rural villages. Then on to the popular volcanic island of Santorini.

Susan is as adventurous and intrepid as I am and despite all the unexpected things that happened during our unplanned itinerary, she never lost her enthusiasm to explore and enjoy new experiences each day.

I was fortunate to interview local marine scientists who were conducting research on the ecology of the Mediterranean Sea and endangered marine species such as sea turtles and the monk seal. I spoke to Greeks from many walks of life, fishermen in the ancient harbors of Crete and Rhodes. We met farmers in the rich, green valleys of Crete and Naxos. I chatted with university students who I met casually in different cities and who were willing to talk to a curious foreign traveler about their studies and hopes for a successful career in a struggling Greek economy. I conversed with many hotel workers and tour staff about their thoughts on how to protect Greece beautiful natural environment from the pressures of rapidly increasing tourism.

We visited Piraeus, the commercial seaport of Athens, where the busy harbor is crowded with cargo ships loading and unloading.

In Crete we spent several days in both Heraklion and Chania, the lovely historic port cities on the islands north coast, known for their magnificent forts, harbors and palaces built by the Venetians in the 16th Century.

Heraklion Crete

We departed from Heraklion and headed south across the big island of Crete. I maneuvered our little Peugeot car up the windy roads and across the mountains of central Crete, through steep rocky passes, some more than 8,000 feet high, then descended through the rich green valleys where pleasant orchards of olive trees covered the hills as far as one could see.

We stopped along the winding roads alongside groves of big, handsome olive trees with wide spreading canopies and branches full of ripe, dark olives, ready for the fall harvest. Men and women worked busily beneath the trees, using long sticks to strike the loaded branches above, so the olives fell from the limbs onto tarps spread out on the ground below. They gathered the olives into large sacks and brought them to barns where the noisy machinery of olive presses crushed the ripe olives into a clear, rich flavorful oil for which Crete is famous.

Olive Orchards

The majestic natural beauty of Crete was at times overwhelming, heading south and passing over the high, rocky mountain ranges, then down again through the dramatic deep gorges. After two days of leisurely exploring, we finally reached Cretes’ less traveled south coast with high cliffs overlooking the sparkling turquoise sea below. For several days, we drove eastward along the winding southern coastal road, rounding mountains above the sea and stopping in small fishing villages to eat and overnight.

South Coast of Crete

We flew from Crete to Rhodes where we spent ten days on the beautiful and historic island and drove across its full length. We started in the harbor city of Rhodes, whose old section is built of sprawling late medieval fortifications. A few hours drive from Rhodes we arrived at Lindos, the ancient coastal town, where classical ruins of a Greek temple sit dramatically atop a high mesa overlooking the sea. The town’s small medieval church was built on the steep mountainside above the semicircular harbor and sandy beach below. The church was filled on Sundays with the faithful, many were women dressed in all black with shawls covering their heads.

Lindos Rhodes

Above all we were impressed by the warm welcome and graciousness of so many Greeks we met. They were open and very kind and were quite willing to engage cheerfully with strangers like us and share something of their lives.

The Rise in Tourism Impacts Sensitive Natural Areas

Tourist visits have increased sharply in Greece and much of the rest of the Mediterranean’s popular coastal areas including in Spain, and Italy during the last thirty years. The Mediterranean coast is one of the biggest tourist destinations in the world, visited by 400 million annually. But tourism has taken a toll on the Med’s natural environment and is contributing to the threat of extinction of rare marine animal species, such as the Mediterranean monk seal and loggerhead sea turtle, the giant sperm whale and common porpoise.

The prolific construction of tourist facilities and infrastructure is often built on coastal zones along the most sensitive marine environments with poor planning, overuse of scarce local resources such as fresh water, and discharge into the sea of sewage, much of it untreated.

The Mediterranean basin is comprised of 23 countries that share its long coastline, including the island nations of Cyprus and Malta. It has been a great challenge in recent decades for the many countries whose coasts surround the Med Sea to reach a consensus on how to protect and preserve its rich and unique natural environment, and to adopt and implement policies that limit pollution, overfishing, and preserve its sensitive coastal zones.

In those instances when consensus has been reached among the Mediterranean’s many national jurisdictions and the European Union, such as the Natura 2000 Program, established in 1992 to protect and preserve terrestrial and marine habitat, too often the programs have not been effectively implemented, monitored, or enforced. So called marine protected zones, such as in the Adriatic Sea on the eastern shore of Italy, have been termed by critics as mere paper zones dedicated only a map. They have no real protection from overfishing and destructive bottom trawling from the national jurisdiction that is charged with their preservation.

Many countries in the Mediterranean, and Greece in particular, have struggled merely to stay afloat economically during the past few decades. Greece was crippled by the devastating 2007 – 2010 debt crisis and the downturn during the Covid epidemic from 2019 to 2021, from which the country is just beginning to recover. The exploding tourism industry has been an economic lifeline to Greece and is now the largest source of foreign currency. One in five Greeks work in tourism. But the sharp rise of tourist visits to Greece, 32 million every year, almost three times the size of the Greek population of 11.5 million, is placing great pressure on Greece’s natural resources and unspoiled coastal and marine habitats.

On Santorini

What will tourists come to see and enjoy in popular destinations such as the islands of Santorini and Mykonos that have highly urbanized zones, where traffic jams and blaring noise are unavoidable, and the quaint towns and beautiful natural features that tourists have come to see, have been degraded or destroyed? How will mass tourism negatively impact not only the natural environment but also the rich traditional culture of Greece, the warm welcome shown by its people to visitors and the colorful dance, music, and cuisine that many travelers come to experience?

The Mediterranean Sea: A Unique Body of Water

The Med Sea is a semi-enclosed body of water, 4,000 km long, measured from the Strait of Gibraltar to Turkey’s southwest coast. It has several deep marine basins in the western side. The Med’s average depth is 1,500 meters.

The Med Sea rapidly loses water through evaporation, and the many rivers that flow into it, the Nile being the biggest, and also the rivers, Ebro, Rhone, Tiber Po and Maritsa, have insufficient flow to replenish its volume. Consequently, there is a continuous inflow of water from the Atlantic Ocean through the Strait of Gibraltar. The incoming water flows eastward across the Med Sea in a belt of surface current that runs along the north coast of the African continent. The surface water gradually turns more saline from evaporation, especially during the summer months. This increases the density of the water, and it sinks as it reaches the eastern Med along the coasts of Israel, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey. Then it begins its flow as a subsurface current in the opposite direction, westward and back toward the Gibraltar Strait, taking between 80 and 100 years for each drop of water to recirculate back into the Atlantic. This slow circulation of currents inhibits the efficient flushing out of pollutants from the Med.

Crete South Coast

This semi-closed system of the Med, combined with the increasingly hotter and dryer climate on the land masses surrounding it, from North Africa to Spain and Turkey, have contributed to its water temperatures rising more rapidly in recent decades than most oceans in the world. Climate change will soon rank with pollution in the coming decades as a major threat to the Med Sea’s health and the many animal and plant species that live in its waters and along its coast.

The Mediterranean Has a Rich and Unique Population of Native Plants and Animals

Because the Med is at the juncture of the land masses of Europe, Asia and Africa, its terrestrial and marine flora and fauna have been influenced by the migration of species from those three continents. The Med is home to a rich and diverse population of terrestrial native plants and animals.

There are approximately 25,000 plant species in the Med basin, of which more than 50% are endemic to the region – they live nowhere else on the planet. The Med rivals the world’s tropical rainforests for rich plant diversity.

Much of the Mediterranean region was once covered in large stands of conifer forests. Human settlement throughout the Med, beginning at least 6,000 years ago, greatly impacted its original flora and fauna. The large forests of Oak, Pine, and the famed Cedars of Lebanon, were felled beginning in ancient times for ship building, and construction of palaces by the oldest civilizations in Crete, Babylonia, Israel, and Egypt. Other emblematic trees are the Argan tree, found in southwest Morocco and the Cretan date palm of Greece and western Turkey.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has deemed the Med as a biodiversity hotspot. Though the Med comprises less than one percent of the world’s ocean surface area, it is home to between 10,000 and 12,000 marine species and has seven to ten percent of the world’s marine biodiversity.

Endangered Wild Kri-Kri Goats Crete

Mediterranean-type ecosystems are also found on the west coast of California, along Chile’s Pacific coast, a small portion of the coast of South Africa and in the southern zones of the continent of Australia. Med-type ecosystems comprise only two percent of the Earth’s land surface on those five continents, but they contain an astounding twenty percent of known plant species. Only tropical rain forests have a higher density. Med-type ecosystems are among the most threatened in the world.

Rich Biodiversity of Greece

Despite Greece’s small size of 131,000 sq. km, which comprises only three percent of the EU territory, it is home to thirty-two percent of known animal and plant species in Europe and contributes significantly to the region’s biodiversity. This is partly a result of the land mass of Greece being at the junction of three continents, Europe, Asia, and Africa, each with its own climate, flora and fauna. Also contributing Greece’s rich biodiversity is its complex paleographic history and geographic heterogeneity with a fragmented landscape that includes high mountain ranges in Greece’s mainland and its larger islands and the isolation of many islands in the Greek archipelago. This caused many unique plant and animal species to evolve in relative isolation.

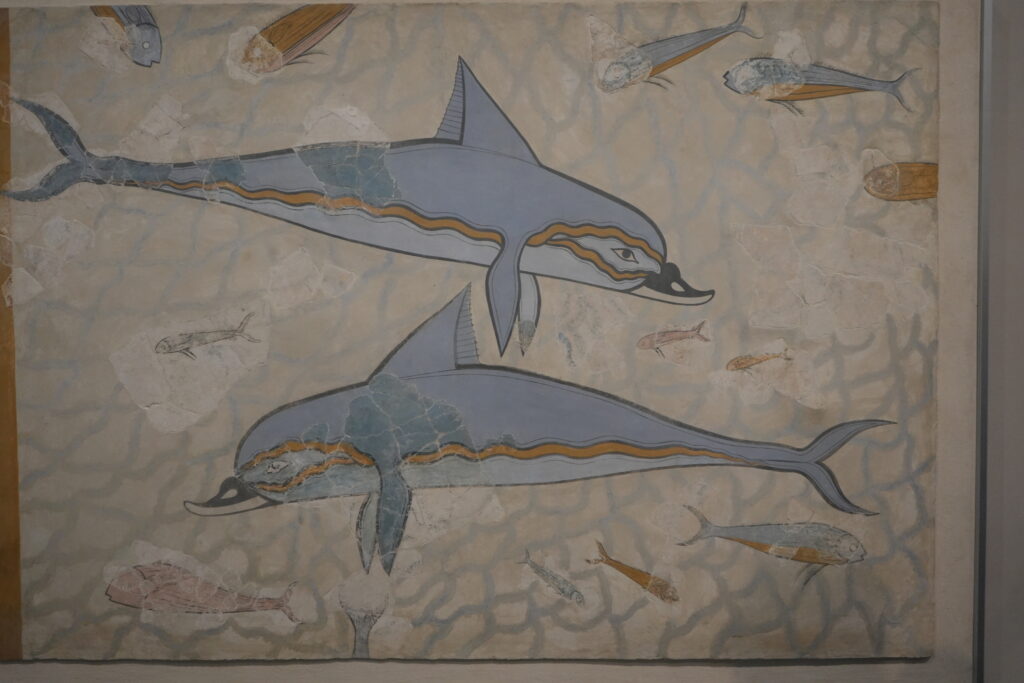

Dolphin Mural Knossos Crete

According to the IUCN, Greece has the second highest number of threatened species in Europe and in the Med, only after Spain.

Pollution Threatens the Mediterranean

The Med

The Med’s natural environment, in particular its coastal zones, have been under increased pressure since the 1960s and even more so in the past two decades. During that time, the Med has experienced an economic boom with rapid expansion of urban areas, growth of transportation, roads, tourism, heavy industry, and shipping. Large industrial farms are replacing small family farms that had a much lower impact on the coastal environment, freshwater lakes and rivers, wetlands, and the adjacent seas.

The biggest source of pollution to the Med Sea is the discharge of sewage from industry and urban areas, University of Athens chemist, Athanasios Valeramides, reported. Each year the Mediterranean receives about 650,000,000 tons of sewage, much of it untreated, 129,000 tons of mineral oil, 60,000 tons of mercury and 3,800 tons of lead and other heavy metals.

The World Wildlife Fund, in a recent report, found that the Med Sea is polluted by about 730 tons of plastic waste each day. Plastics account for more than ninety-five percent of floating litter and more than fifty percent of litter found on its seafloor.

Research in the journal, Scientific Reports, showed that up to eighty percent of the plastics that pollute the Med, come from recreational use of the region’s beaches.

The amount of sea surface microplastic per square kilometer in the Med is about two- and one-half times higher than the amount found in most areas of the world’s oceans. The Med has less than one percent of world’s oceans but contains a frightening seven percent of its microplastics.

The Med has very busy of shipping traffic, much of it passing from the Red Sea through the Suez Canal and through the Strait of Gibraltar, gateway to the Atlantic. Many large ships that traverse the Med’s busy sea lanes purge their dirty bilges, holding tanks and ballasts. This also transports harmful invasive marine species to the Med from other oceans.

The Greek government has recently approved the purchase by COSCO Shipping, a Chinese government-owned company, of sixty-seven percent of Greece’s largest port of Piraeus, as part of its Belt and Road Initiative to expand its trade and economic influence on several continents. The implications for China’s growing geopolitical and military ambitions cannot be overlooked in its purchase of not just Piraeus, but major seaports in many countries around the world. Piraeus is one of Europe’s main ports for the heavy ocean traffic, that moves cargo between southern Europe and Asia, and with its recent purchase by China, marine traffic is expected to increase even more, further compromising the health of the Med Sea.

Large scale farming in coastal zones creates run off nitrogen and phosphorous that causes ocean eutrophication, a reduction of oxygen levels, that are vital to the health and survival of marine plants and animals. Increased temperatures in the Med Sea also contribute to its reduced oxygen content. This leads to smaller size fish that cannot not take in enough oxygen to thrive.

Agriculture uses seventy-five percent of the freshwater available to the Med region, and leakages and inefficient use of water in urban areas contribute to the critical problem of scarcity of fresh water.

Sixty-five percent of Greece’s wetlands have been lost due to drainage and diversion, mainly to expand farmland. These unsustainable practices, combined with the region’s low average rainfall is causing desertification and land degradation in many areas of the Med. Agricultural productivity in the region is expected to decline significantly this century, a time when the demand for food crops is rapidly increasing as the world’s population grows beyond 8 billion.

The Mediterranean Sea and Land Temperatures are Rapidly Increasing

The Med Sea and its coastal zones are among the most rapidly heating areas of the planet. Sea temperatures in the Mediterranean from Barcelona to Tel Aviv are reaching record highs every year. This will increase pressure on the Sea’s marine species.

The record heat in the atmosphere above the Med’s coastal land masses including scorching zones of north Africa, combines with the rising temperatures in the Med Sea itself, creating a vicious cycle of extreme heat events. In July of 2023, Europe’s land mass saw record temperatures, 45 C (113F), caused in part by a heat dome, including over parts of Greece, Spain and Southern Italy. In July of 2023, the trapping of greenhouse gases from human activity caused the Earth’s highest average temperature ever recorded, 17.3 C (63 F). The Med Sea also had the highest temperature ever recorded; the surface sea temperature was 28.4 C (83.1 F).

According to the First Mediterranean Assessment Report, written in 2020, by an independent group of 190 scientists from 25 countries, the combined land and sea temperatures in the Med have increased by an average of 1.5 C degrees since the advent of Industrial Revolution, compared to an average increase of 1.2 C degrees on the rest of the planet’s combined land and sea surfaces. The Report predicts that temperatures in the Med will increase above present levels by a frightening 3.8 C to 6.6 C degrees by 2100, if greenhouse gas emissions continue at current levels with “business as usual.” That would be an unsustainably high temperature for plant and animal life and many species will not be able to adapt and migrate to cooler regions. Since the Med Sea is a semi closed system it would be especially difficult for its marine life to migrate to regions with cooler ocean temperatures.

Harbor Chania Crete

Assuming there could be a drastic reduction in worldwide greenhouse gas emissions in conformity with the unfulfilled pledges made at the 2015 Paris Climate Accord – a hopeful but unlikely scenario – scientists predict that the temperature in the Med will continue to rise above present temperatures, between 1.8 C and 3.5 C degrees by 2100, still a dangerously high temperature.

Massive mortality of marine species in the Med that occurred between 2015 and 2019 was caused by extreme heat waves, according to Juaquin Marabou, a researcher at the Institute of Marine Sciences at Barcelona. He was part of a team of scientists who found that colonies of many marine species along thousands of miles of the Med’s coastal zone, including corals, sponges, and seaweed, were severely impacted by rising temperatures, with many large colonies dying.

Gil Rilov, a scientist at Israel’s Oceanographic and Limnological Research Institute, reported that the hottest parts of the Med are in the eastern zone, along the coasts of Israel, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey, where he found the conditions particularly dire. Many native species are being driven to the brink because every summer their optimum temperatures are being exceeded. Rilov observed that deep sea mollusks have been devastated in the eastern Med. He found that the waters of western Med Sea, like the eastern region, are also experiencing extreme heat, measured down to depths of 50 meters. Rilov predicts that in the coming decades, the central and western Med areas of Italy and Spain will also experience a significant loss of biodiversity from an increase in land and sea temperatures.

A team of researchers including Stelios Katsivalis, professor at the University of the Aegean, presented a research paper, “The Status of Coastal Benthic Ecosystems Evidence from Ecological Indicators,” in 2019, in which they explained that the Med Sea is unique, despite its relatively small size, because of the large number of unique marine habitats and native species and the overall diversity it hosts. But, they warned, the Mediterranean is one of the world marine environments most vulnerable to human caused pressures.

Rethymno Crete

Mediterranean Seabed Meadows are Disappearing

Posidonia oceanica seabed meadows, grow abundantly across many areas of the Med Sea floor at a depth of 1 to 40 meters where sunlight can still penetrate. The rich habitat created by the seabeds also cover much of the sandy sea bottom along the coastal zones of the Greek mainland and its many islands.

In the dense Posidonia seabed meadows, fish lay eggs and juvenile species can find refuge and protection from predators. More than 500 species of vertebrates and invertebrates live in the seabeds exclusively, and since they provide food for many fish, crustaceans, and mollusks, they are the most productive fishing areas in Greece and the other countries that share the Med Sea.

The seabed’s deep roots help stabilize the sea floor from erosion, and they produce vital oxygen through photosynthesis. The Barcelona Convention for the protection of the Med Sea has designated Posidonia as a protected marine plant species.

Besides coastal development, pollution and increased temperatures, the seabeds in the Med are under threat from commercial fishing boats that bottom trawl, dragging nets with large weights that tear up and destroy the beds on the sea floor. The seabeds in the Med have already lost full thirty-four percent of their total area.

The seabeds also have an important function as a carbon sink, storing vast amounts of carbon dioxide, the most prevalent of the harmful fossil fuels that are heating the atmosphere.

When the seabeds are bottom trawled, not only in the Med Sea, but a practice that occurs throughout much of the world’s oceans, the sea floor is disturbed and the large amounts of carbon dioxide, that have been sequestered for thousands of years in the seafloor sediments, are released. The amount of CO2 released annually from the Posidonia seabeds from bottom trawling is enormous, equivalent to the amount of CO2 emitted each year from all the world’s air transportation.

Depleted Fish Stocks in the Mediterranean

One of the biggest challenges facing the Med Sea, and especially Greece, during the past twenty years, has been the steep decline of fish stocks from overfishing, beyond levels that allow for their natural replenishment.

We hired a 35-foot fishing boat in the main harbor of Rhodes for a day excursion along the adjacent rocky coast, lined with sandy beaches and small coves. The boat captain, Andres, a tall, lean man of about fifty, comes from a local family that has relied on commercial fishing for generations. He explained why fish stocks were depleted. “It has become harder and harder to catch enough bottom fish and tuna to make a living,” he remarked, with a bitter smile as he peered ahead steering his boat. “In the last 20 years, we have lost almost all the fish around Rhodes and in Greece. It’s like a bomb that has dropped, they are all gone,” he said visibly exasperated.

Fishermen Heraklion Crete

I peered across the mild blue sea. It was a beautiful sunny day; the waters were smooth. Andres’ boat plied comfortably ahead, finally reaching a small, protected cove where we tied up to a buoy and I dove into the warm October sea to swim and snorkel. The bright aquamarine water sparkled magically below. Schools of small fish darted between huge boulders on the sea floor.

Later in the day as Andres piloted his boat back to Rhodes harbor, we could see two big Greek navy ships cruising a few miles to the east, patrolling the narrow strait between Rhodes and the mountainous, brown, southern Turkish coast, only 18 km distant. No doubt the ships were keeping a look out for foreign commercial fishing trawlers illegally encroaching on Greek waters, as well as searching for boats secretly ferrying illegal Syrian immigrants embarking from the Turkish coast in hopes of reaching Rhodes.

As he steered the boat back to the harbor, captain Andres lamented, “It’s the large fishing boats from Turkey, Greece, and other countries, that have long nets they drag behind them. For years, they have fished the waters around Greece until there is nothing left. Now they are all gone. No more fish. Only a few little ones we catch and sell. Some days I go out tuna fishing and if I’m lucky can bring back some medium sized ones. The big ones are mostly gone.”

I asked Andres whether it is the large commercial factory ships or the small fishing boats that have depleted the fishing stocks. “Its both, the big and the small boats,” he said, “finished, commercial fishing in Greece for people like me is over,” he declared emphatically with a dramatic upward gesture of his hand.

These days captain Andres manages to earn a little money with his boat taking tourists out on day excursions.

The European Commission’s Joint Research Center found that ninety-three percent of the Mediterranean fish stocks are overexploited, and some have completely disappeared as they are fished at levels so intense, they do not allow for natural regeneration.

According to the World Wildlife Fund 2019 Report on the Med, during the past fifty years, the Med Sea has seen eighty percent of its fish stocks overfished and lost thirty-four percent of its total fish population. Marine mammals, including whales and porpoises, have decreased by forty-one percent. This compares with an average of thirty-three percent of fish stocks that are overfished in the rest of the world’s oceans, also a very concerning level.

Fish Market Athens Greece

Marine scientists agree that the Med is the most overfished sea in the entire world. Sixty percent of seafood consumed in the Med must be imported. When I inspected the fresh fish for sale in open air markets in Athens, Rhodes, and Crete, I could see that fish are generally very small size. Studies have shown that since 1950 fish have shrunk an average of twenty to thirty percent in size, from decreased oxygen levels in the Med Sea.

There is less abundance of fish and also less variety of species. Some of the stocks that are overfished in the western Med are the anchovy, red mullet and stripped red mullet, turbot, black bellied monk fish, poor cod, red prawn, sole, blue whiting, and black mullet, and several species of prawn. The most overfished species is the hake.

As mentioned above, the greatest cause of overfishing is bottom trawling, that despite official prohibition by several Med countries, is still prevalent in several areas, and one of the worst is off the east coast of Italy in the Adriatic Sea. Bottom trawling, the indiscriminate dragging of large gear across the seafloor, destroys sponge and coral habitats and leaves the bottom as an expanse of lifeless sand and rubble. The bottom trawlers are unselective and sweep up everything in their paths. The trawlers keep about three percent of the fish caught and the rest, comprising more than 100 species, are thrown back dead into the sea as by-catch.

The Mediterranean Monk Seal and Loggerhead Turtle

Two of the iconic species found in the Med Sea are the loggerhead turtle, classified by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as endangered, and the Mediterranean monk seal, which is listed as extremely endangered.

Vivian Louizidou, marine biologist at the Hellenic Center for Marine Research in Rhodes and doctoral candidate in marine sciences at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, took the time from her busy schedule to explain to me her work at the Center to protect marine species including the monk seal and the loggerhead turtle.

Careta Careta Sea Turtle

Vivian is in her mid-twenties, and despite her youthful appearance, her extensive knowledge about marine species in the seas around Greece, became immediately apparent. She is passionate and articulate about her research and work to protect endangered marine animals.

“On my Ph.D. I focus on the general habitat of Rhodophyta (red algae) species,” Vivian explained, “but our work in the Aquarium is also about the endangered species of Monaches monaches seals, the monk seal, the Careta careta, the loggerhead sea turtles, and some marine mammals as well.”

“The monk seal, which is also a protected species, is called Monachus monachus, because the collar of the seal looks like a Catholic priest, like monks,” she pointed out smiling. “Also in Greek, Monachus means monk. It is a species that likes to be solitary, like a monastic monk,” she explained.

“Of the monk seals,” she told me, “there are only 700 individuals around the world and 400 of them live in Greece. So, it’s very important to protect them, the habitat, and the general ecosystem.”

I was astounded that so few monk seals survive in the entire world, with only 700 and half of them in Greece.

I learned that the adult seals used to populate sandy beaches in the Med where they gave birth, and like all mammals, the mother seals nursed their pups with milk. But hunting and other interference by humans caused them to retreat to remote sea caves where they congregate, mate, and give birth to their young. The caves offer protection from human encroachment but pose certain risks for the young seals, including strong waves and currents which may cause them to drown.

In the last two centuries there were hundreds of thousands of monk seals in the Med, but they were hunted almost to extinction for their fur and oil content. Vivian and other scientists at the Center conduct research on the remaining small population of the seals and work to protect them by teaching fishermen, and tour operators to stay away from the seals and their habitat

Mediterranean Monk Seal

Vivian explained, “When they have their babies, in sea caves, it is very important that we do not go there with a boat, with tourists or whatever to interrupt their reproduction activities, or their babies. They are marine mammals, so they nurse their babies, and they need to be left alone, and quiet. Which is kind of difficult because of the high tourist activities.”

I asked Vivian to tell me about the migration of the loggerhead turtle, where they go, where they lay their eggs, whether in Turkey or Greece and what is threatening their survival.

“The Careta careta sea turtle species is found all around the Med,” she explained. “They lay their eggs in sandy beaches, especially in Zakynthos, among the Ionian Islands on the west side of Greece, where there is a very big nesting site of these turtles, but also in Crete and Rhodes Island, and the coast of Turkey there are many sites, where they nest, where they lay their eggs.”

“What is the migration of the turtles?” I asked.

“Well, the turtles, they are known to go back to the same place where they hatch, and lay their eggs on the same beach, after many years, so it’s very important to protect their habitat, especially because of the overgrowth of tourists and the expansion of the building activities near the coastline.”

“It’s very important to protect these locations, so the turtles after ten or twenty years, they can come back again and lay their eggs at the same location. They have specific locations where they go year after year, and they know exactly where to go, she said with visible excitement.”

“What are the things that you are most concerned about that are affecting the loggerhead turtle?” I asked.

“I think habitat loss is very important especially because of the tourist activities,” she said.

“These turtles, they get out of the ocean during the night, so they arrive at the beach, and they lay their eggs.”

“So, when the new turtles hatch and they want to get back to the ocean, they get confused from the light on the land.”

“This is why it is important where the turtles are nesting, it is prohibited for the beach bars and restaurants to have light that shines directly on the sand, so the new the turtles can go back to the ocean and not get disoriented.”

“Have you had any success seeing the populations of turtles increase?” I wondered aloud.

“In the island of Zakynthos, the population of turtles is in very good shape,” she replied enthusiastically.

“Also, in Rhodes we have a few nesting locations, that they seem to go very well. We have found some nests in new locations.”

“So, tourism has been a big problem, building along the coasts,” Vivian explained.

“What success have you had educating tourism enterprises?” I asked.

“The Rhodian Association of Hoteliers is very eco-friendly, I would say. Most of the hotels in Rhodes, especially the big ones, have come a long way in protecting the environment, so they have a lot of programs to reduce plastic waste, with discharging wastewater, and educating their guests, that if you see a turtle or a monk seal you don;t go close, you don’t do anything with the animals.”

“There is also a new activity at the moment with the fishermen, because of the overfishing and all of the damage that it causes to the environment, there are some new tourist activities.”

“The fishermen take the tourists on fishing trips, which is a very interesting thing. The boat owners can educate the tourists about what we have in our seas, how we can protect them, why we should stop overfishing of the seas, and everything.”

I asked Vivian, “Has there been any success in Greece in creating marine protected areas?”

She explained, “Quite recently, the island of Yaros, which is quite close to Crete, has been set as a no take zone, as a marine reserve. For a few years there will be a complete absence of people, fishing boats, tourist activity and everything, since on this island it is a very healthy ecosystem with a lot of Posidonia sea grass beds, and nursing grounds, so it is a very good starting point for the rest of Greece.”

“Vivian, we are in the place of your home, the beautiful island of Rhodes. Tell me how you became interested in marine sciences?” I inquired.

Vivian Louizidou, marine biologist at the Hellenic Center for Marine Research in Rhodes and doctoral candidate in marine sciences at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland

Her face lit up and she replied enthusiastically, “I was interested in the environment in general, and when I was in my third year of studies for my bachelor’s degree, there was a position, for my thesis to be conducted on Rhodes on a fish farm, to discover, to understand, the species that live there under the cages of the fish farm.”

“So, I said, why not, I am from Rhodes, and I met the right people that helped me realize that I wanted to work in the environment, the marine environment, and all of the sustainability efforts about how to protect the ecosystem.”

I asked her, “So, you see a very rewarding and exciting future for yourself staying at the Aquarium in Rhodes?”

“What excites me more is to educate new, young students on how to protect the environment. How to be more conscious about what we do that can affect the environment.”

“This is a new generation. We need their support. They can do something to make a bigger change,” she exclaimed, her eyes sparkling with optimism.

“I think research is very important for new knowledge, but I think it should be combined with educating the people, the citizens, how to do the best for sustainability of the environment.”

“We also try to do more of these projects through the Hydrobiological Station of Rhodes which is part of the Hellenic Center for Marine Research,” Vivian explained.

“So, it is important to educate tour operators, hoteliers, the government, everyone so all together we can have a better future.”

With dedicated, young marine scientists like Vivian, who conduct vital research on how to preserve marine habitat and protect threatened species, and who educate the public to promote these policies, there is cause for optimism about the future of the Med Sea.